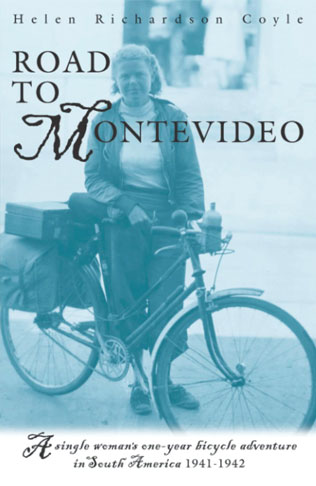

Helen Richardson Coyle

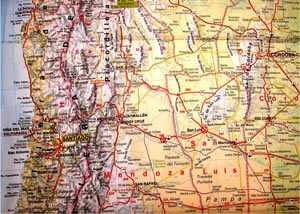

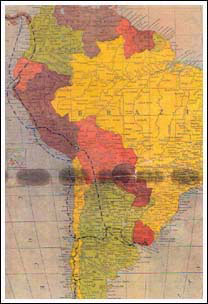

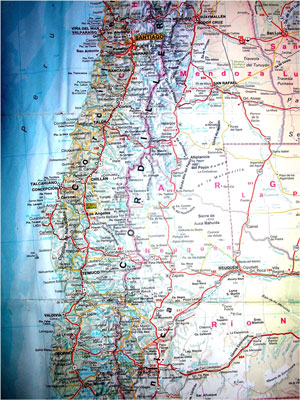

Helen Richardson, a single woman of 27, embarked on a very unique adventure on November 21, 1941. With war raging in Europe and about to begin in the Pacific, she set sail from San Francisco, California, in a banana boat for South America, where she would spend a year cycling on her own. First a short trip through Panama and then on to Valparaiso, Chile, where she began a much longer journey that would take her over the Andes, across the Argentine Pampas to Buenos Aires and finally to Uruguay. Her trip was abruptly cut short in Uruguay, where she was detained for two weeks in Sept. 1942 on suspicion of being a Nazi spy. After 6,000 miles of cycling, she was ordered to return to the United States by the U.S. State Department, thus ending a year early her planned two-year adventure.

Helen Richardson, a single woman of 27, embarked on a very unique adventure on November 21, 1941. With war raging in Europe and about to begin in the Pacific, she set sail from San Francisco, California, in a banana boat for South America, where she would spend a year cycling on her own. First a short trip through Panama and then on to Valparaiso, Chile, where she began a much longer journey that would take her over the Andes, across the Argentine Pampas to Buenos Aires and finally to Uruguay. Her trip was abruptly cut short in Uruguay, where she was detained for two weeks in Sept. 1942 on suspicion of being a Nazi spy. After 6,000 miles of cycling, she was ordered to return to the United States by the U.S. State Department, thus ending a year early her planned two-year adventure.

Helen was born in California in 1914 to Martha and Walter Richardson. Both of her parents were of prominent lineage: her mother was a Bebb, daughter of a noted botanist and the granddaughter of William Bebb, the Governor of Ohio in 1984 – 1849 and an appointee in the Lincoln Administration. A first cousin on her mother’s side, Norman Mason, was Administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency during the Eisenhower Administration. Her father was an eastern transplant whose uncle, John Pierce, was a founder of the American Radiator and Standard Sanitary Co. (now American Standard Co.). Pierce had no children and willed part of his fortune to his stepsister, Helen’s grandmother Richardson. This legacy was a source of family wealth that helped support Helen’s travels at a time when others were struggling to make ends meet.

Helen grew up on a citrus ranch outside the small town of Porterville, on the eastern edge of the San Joaquin Valley and in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

Helen grew up on a citrus ranch outside the small town of Porterville, on the eastern edge of the San Joaquin Valley and in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

She got the travel bug from her family, particularly her father and two brothers. Her father traveled extensively in California and the Sierras and worked as an engineer for several years in the gold mines of South Africa, circling the globe going to and coming from South Africa in 1897 – 1903. One of her brothers, William, was a member of the Archbold Expedition to New Guinea in 1938 – 1939. Her older brother, Hilton, traveled extensively in Central America and Africa and encouraged his younger sister to join the boys on camping trips in the Sierras. Helen herself had already cycled in Europe (July – December 1939) and in Japan and China (June – August 1940) before her trip to South America.

Her father gave her encouragement and financial support. When she was considering a choice between work and a South American jaunt, her father advised…

Get your South American trip first. That is my advice. For why? Because you can always get a job, but you can’t always go to South America. For why? – One look at your brothers and sister tell the tale. They can’t travel now because of jobs, family, etc., etc., etc. Sabe? Some people better stay home than travel, but not you. You will be a better teacher or anything you may want to do for having had it. You will learn better how to live and enjoy what you have by seeing how others do it.

In preparation for her trip, she gathered together a variety of documents to assurea successful trip, including a passport, membership cards with the American Bicycle League and the Pacific Northwest Cycling Assn. (Seattle Chapter), a 1941 pass for the American Youth Hostels, documents of good health, and a certificate of inoculation against cholera. She also carried letters from the Bank of America, vouching for her financial responsibility as “the daughter of one of the most substantial local citrus growers,” and from the City of Porterville, certifying that she was a person of good moral character and principle” and had never violated any laws or ordinances. She also meticulously planned what clothing and other effects to carry with her since she was seriously constrained by a small set of saddlebags and a diminutive overnight case that fit on the back of her bicycle. It was surprising what she was able to pack in those two small pieces: mechanic’s equipment for a bicycle, a first aid kit, and a lady’s wardrobe for all climates and social occasions. She also embarked with a small amount of cash (15 one dollar bills) and $800 in traveler’s checks, which was supplemented later in her trip by an additional $1000. Her bicycle was a Raleigh three-speed, which she named “Chester,” after the English town where she bought it two years before.

In preparation for her trip, she gathered together a variety of documents to assurea successful trip, including a passport, membership cards with the American Bicycle League and the Pacific Northwest Cycling Assn. (Seattle Chapter), a 1941 pass for the American Youth Hostels, documents of good health, and a certificate of inoculation against cholera. She also carried letters from the Bank of America, vouching for her financial responsibility as “the daughter of one of the most substantial local citrus growers,” and from the City of Porterville, certifying that she was a person of good moral character and principle” and had never violated any laws or ordinances. She also meticulously planned what clothing and other effects to carry with her since she was seriously constrained by a small set of saddlebags and a diminutive overnight case that fit on the back of her bicycle. It was surprising what she was able to pack in those two small pieces: mechanic’s equipment for a bicycle, a first aid kit, and a lady’s wardrobe for all climates and social occasions. She also embarked with a small amount of cash (15 one dollar bills) and $800 in traveler’s checks, which was supplemented later in her trip by an additional $1000. Her bicycle was a Raleigh three-speed, which she named “Chester,” after the English town where she bought it two years before.

Many years after her bicycle journey in 1941 – 1942, she married William E. Coyle and had six children (Anne, William, Walter, Richard, Marti, and Rob). She passed away in 2003.

Many years after her bicycle journey in 1941 – 1942, she married William E. Coyle and had six children (Anne, William, Walter, Richard, Marti, and Rob). She passed away in 2003.

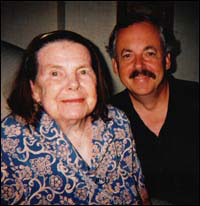

Sitting comfortably in her wheel chair in an Arlington nursing home, you’d have no idea Helen Richardson Coyle was once kicked out of Latin America on suspicion of being a spy.

Sitting comfortably in her wheel chair in an Arlington nursing home, you’d have no idea Helen Richardson Coyle was once kicked out of Latin America on suspicion of being a spy. “I didn’t plan on anything. I just had my idea of seeing the country and pedaling my bike,” Coyle, now 86, recently told SPOKES.

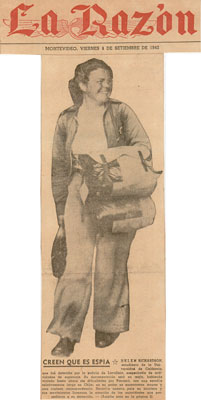

“I didn’t plan on anything. I just had my idea of seeing the country and pedaling my bike,” Coyle, now 86, recently told SPOKES. After leaving the Andes she headed for Cordoba, Argentina, where she encountered another trend of her trip: police asking lots of questions. As war had now moved to the Pacific, authorities had grown more suspicious.

After leaving the Andes she headed for Cordoba, Argentina, where she encountered another trend of her trip: police asking lots of questions. As war had now moved to the Pacific, authorities had grown more suspicious. By the next morning the bicycling “North American spy” was on the front page of all of the city’s newspapers. Coyle spent the next 10 days dodging photographers as she fought to be allowed to continue on her journey.

By the next morning the bicycling “North American spy” was on the front page of all of the city’s newspapers. Coyle spent the next 10 days dodging photographers as she fought to be allowed to continue on her journey. The two moved to Washington in 1945 where he worked for the Washington Star and later for the Washington NBC affiliate as director of advertising and public relations. Helen Coyle settled down to life as a full-time mom to six children.

The two moved to Washington in 1945 where he worked for the Washington Star and later for the Washington NBC affiliate as director of advertising and public relations. Helen Coyle settled down to life as a full-time mom to six children.